This Lebanese Art Dealer Turned His Home into a Living Gallery

Ditching the white walls of traditional galleries, Lebanese art dealer Karim Massoud created a space where art is meant to be lived with - not just looked at.

When the 2020 Beirut blast destroyed Karim Massoud’s home, the artworks he had spent years collecting miraculously survived. Forced to sell his work to support his family, what could have been one of the lowest points of his life ended up becoming the most rewarding chapter of his career.

What started as a necessity became something more: a home that doubles as a gallery. Massoud’s space is neither showroom nor museum; it’s a lived-in world where paintings, antiques, and textiles seamlessly blend into daily life. Through his Instagram platform, @BeirutBlackCatArt, the Lebanese art dealer has drawn in a community of collectors and creatives through his informal, inviting approach, proving that art isn’t just something to own - it’s something to live with.

What brought you into the art world?

I worked internationally in large-scale events until 2020, handling everything from weddings and graduations to national receptions for kings and the FIFA World Cup announcement for Qatar. Managing big financial flows, I developed a passion for art early on. While my friends spent on travel and brands, I invested in paintings—often leaving them unframed—just wanting a home full of art.

In 2019, Lebanon’s revolution began, followed by COVID, the banking crisis, and finally, the Beirut blast in August 2020, which destroyed my home. That explosion changed my entire life. Yet, the paintings I had collected remained intact. It felt like a sign. With my money stuck in banks and my home gone, I needed stability, so I started selling my collection at the same prices I had bought them for.

How did you transition from selling your own collection to dealing in art more broadly?

I have a background in interior design and decoration, and after the explosion, I started helping restore apartments that had been damaged. At first, I redecorated homes for friends, then their friends, and eventually for strangers who wanted new art in their spaces.

Selling my own collection was difficult—I had spent ten years curating those pieces—but it became a necessity. Over time, I realised the artworks that had survived the explosion also became a means of financial survival for me and my family. Over time, I found myself positioned between being a major art dealer and running a gallery.

How did you come up with the idea of using your home as a gallery?

I’ve always loved a maximalist space—filled with paintings, antiques, books, and textiles. My home naturally became a gathering place for art, whether they’re for photo shoots or exhibitions. People would joke about “Karim’s museum,” and over time, it just made sense. I knew I couldn’t recreate this energy in a rented gallery space.

How have collectors responded to this unorthodox approach?

At first, there was hesitation—from me, my friends, and even established collectors. “What if it interrupts your freedom? What if people damage something?” But hosting became a ritual I love—day and evening visits where guests share a meal, enjoy a drink, and sit with the art. Some days, I’d have new visitors every 30 minutes, especially when major pieces were available.

Initially, older gallerists dismissed me as the black sheep. Now, we meet for coffee, attend auctions together. They’ve gone from skeptics to friends, and some have even become mentors. This business isn’t something you can master by just reading about it—you have to keep learning every day.

Have any collectors expressed a preference for this setting over more traditional galleries?

Galleries can feel cold—white walls, four paintings, nowhere to sit. They’re hospitable, but something is missing. At my home, guests knock on the door, are greeted by my cats, and can sit wherever they want, with coffee, homemade food, music, even the TV on in the background. Sometimes I even step out, leaving people to live with the art.

This relaxed setting helps sales. I tell clients, "I won’t let you buy unless you’re completely in love—unless you go home and can’t stop thinking about it." This approach makes art feel closer to the heart, the mind, and the home.

How do you connect with artists and source new works?

The art world is unique. Many artists are introverts, and building relationships with them requires patience. Some have strict routines—you might have to go to the bakery where they buy their bread just to track them down and see if they’re in the right mood to talk about their work. It’s an entire universe in itself, and it’s unlike anything I’ve experienced before.

Have you noticed a particular mindset among buyers, especially during times of crisis?

Yes, during crises, people often become more aware of what makes them happy. Some buyers see their purchases as their last major investment, not out of desperation, but because they want to own something deeply meaningful. They fall in love with a painting and make sacrifices to own it—choosing not to go out for a month just to afford it. The uncertainty in the world pushes people to invest in what brings them joy.

During Israel’s attacks on Lebanon, you mentioned people were buying artwork as a final purchase. What kind of work were they seeking?

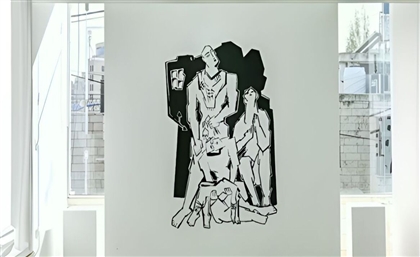

It wasn’t about a specific type of art—it was about certainty. They knew they wanted to own something before things got worse. I sell what I love, and my taste leans towards deeper, darker pieces with stories behind them. My buyers aren’t looking for geometric patterns or landscapes—they want art with a narrative.

For example, the paintings of Johan Adam depict genies from his dreams—philosophical, dark, deep figures. People who come to me are drawn to these stories, and I amplify this connection through my Instagram account, where I share the stories behind Beirut, the people, and the art itself.

You mentioned some collectors took advantage of the crisis by offering extremely low prices. Can you elaborate?

Some big collectors saw the crisis as an opportunity to acquire valuable art at unfairly low prices. A painting worth USD 10,000 would be offered USD 1,500, with the collector pressuring the seller to take the money and flee the country. Some fell for this out of desperation, but I intervened when I could.

One woman had a Paul Guiragossian painting worth USD 70,000 and was being pressured to sell it for USD 10,000 to USD 15,000. I reached out to her through a friend and convinced her to wait until we could get her a fair price.

Do these buyers come from outside Lebanon, or are they local?

From my experience, they are Lebanese. They understand the local mindset and exploit the pressures of war. They aren’t necessarily looking to flip the artwork for an immediate profit—just acquiring it at a significantly reduced price is a win for them.

Many assume the art world is peaceful and collaborative, but you suggest otherwise. How competitive is it?

The art world is not as serene as people think. It’s highly competitive, with dealers and collectors sometimes behaving like sharks. When I entered the business, some older dealers questioned my presence, but I reminded them that they also started young. The difference was that they came from wealthy families with connections, while I built everything from scratch.

Over time, they acknowledged my work as legitimate, paving the way for others who started with nothing.

Do you see yourself evolving this home gallery concept in the future?

This home gallery experience has been marvelous, though it has its downsides. Sometimes, I consider transitioning to a more structured setup—two salons, a dining area, a semi-bedroom, a kitchen—all displayed with art, where I’d still be present but have a bit more personal space.

For now, I want to continue. Five years feels more appealing than six. Maybe in a decade, I’ll expand—perhaps to a larger, traditional Lebanese house with arches and high ceilings.

For the time being, it’s serving its purpose. It’s offering a new perspective on art, making people connect with paintings and artists in a deeper, more personal way. It’s creating a different kind of experience—a space where artists, collectors, and visitors from different backgrounds come together to connect and collaborate.