Palestinian Artist Nour Al Naji Strips Her Journey to the Bone

Skeletal forms are a recurring theme in her design work and practice, a metaphor for the vulnerability and fragility of human form.

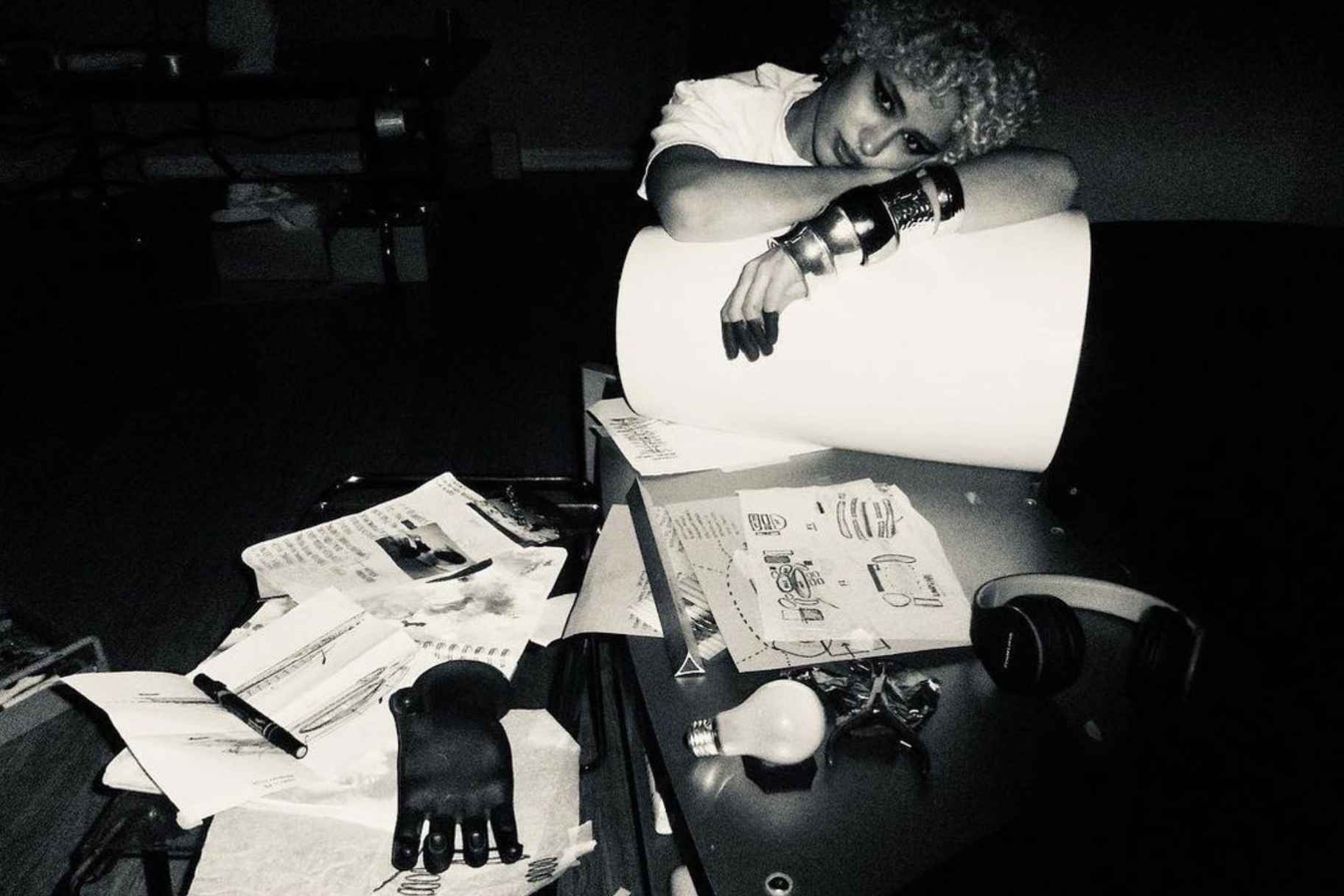

For Palestinian creative Nour Al Naji, everywhere and nowhere is home. An independent artist, fashion designer and creative based in Amman, Jordan, Al Naji expresses through painting, fabric manipulation and prototyping, calligraphy, music and creative direction. Born and raised in Jordan, she immigrated at 17, spent years navigating between countries, and eventually returned home. Her creative journey began early in her childhood.

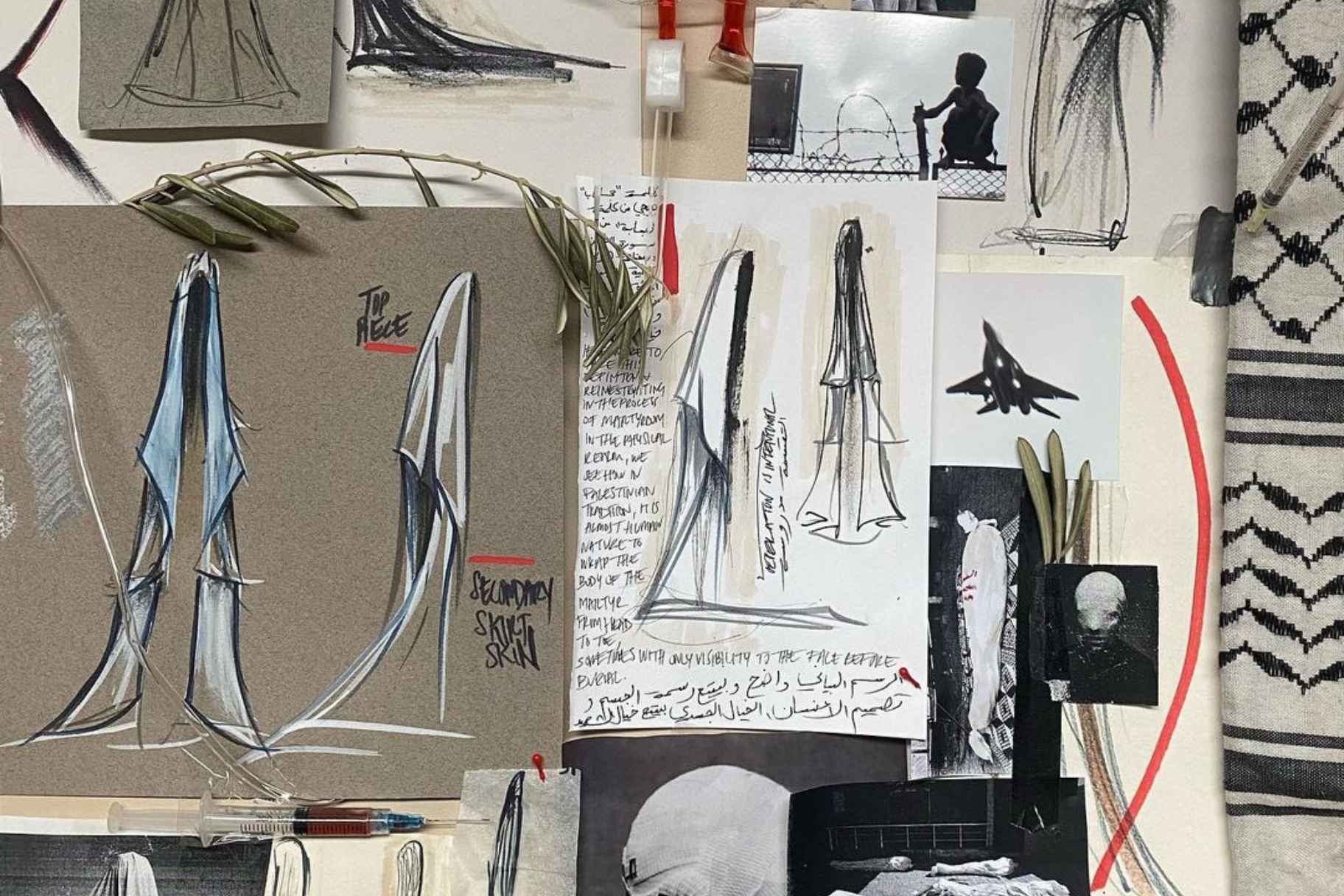

While this journey began with canvas and charcoal, her first official venture into fashion design was the 2023 collection, ‘Apocalyptic Rebellion’. This collection displayed the human form in an exaggerated and distorted lens, through skeletal silhouettes, extraterrestrial undertones and clashing textures, marking her a new artist that should be watched.

To Al Naji, her art is an angular reflection of her homeland’s reality and what she observes as a displaced Palestinian. Blurring the lines between art, design and rebellion, she challenges the viewer to confront the actuality of Palestinian lives under occupation through pieces that are meant to evoke discomfort, and act as a taste of reality for their day-to-day experiences.

The concept of the “human vessel” is a central motif in your work. Can you elaborate on that exploration of the human body?

I draw inspiration from my own body and the world around me. This stems from growing up in Jordan, where the desert sparked both comfort and curiosity. The desert holds a cycle of rebirth—stones and sand persist, while animal skeletons and aged herbs represent both death and immortality. I’ve since always referenced and been protective of that environment and everything it births.

My exposure to Bedouin culture, closely tied to my Palestinian ancestry, made me deeply protective of human nature and the vessel that contains it. This sensitivity is reflected in my designs and process, where I replicate skeletal structures to remind viewers of the intricacy and delicacy we’re built with—and the need to honour and protect ourselves and each other. The world is increasingly dehumanising us, and I will always resist that.

You describe your pieces as embodying “exoskeletal forms”—a symbol of how we’ve stripped ourselves of flesh and reduced humanity to mere bone. What inspired this?

It stems from my desire to remind people that our physical bodies are not metaphors; yet, we treat them as such. There are systems designed to make us feel perpetually incomplete, pushing us to neglect the protection and respect our minds deserve. It's as if you have to pay a fee to be human—otherwise, your trial expires.

Choosing exoskeletal forms in my designs is a literal recreation of what already exists within us, but it’s only praised when it’s transformed into something consumable.

Can you share examples of how you translate this concept into your work?

One example is a design called 005____Sensorium Sleeve, a recreation of the human skeletal hand. It’s a direct representation of my own hand, extracted and placed to be worn. The realism is intentional, conveying that we are not lacking—there’s beauty in what already exists.

Another is my 10-foot painting ‘How Deep Can You Cut?,’ which features a spine-like form but retains its own identity. The sharp edges mimic a knife or broken glass; an interplay about a person/entity/or environments that will go to deep lengths to cut you—all unintentionally reiterated as a spinal form.

The brutalism in your designs seems to respond directly to the “brutalism of the world.” Can you talk about the interplay between the personal and sociopolitical in your creative vision?

The brutalism I reference stems from my experiences in Western environments, which contrast sharply with the values of the Middle East. Human nature is soft and intuitive, yet we are placed in systems that force us to compete with machines—a slow form of murder that many don’t recognize.

My design, 006_____Stone Headpiece, from my debut collection ‘Apocalyptic Rebellion,’ embodies this exact point. It hints at the brutalist desire to compete with technology in exchange for our humanity, as if being human isn’t divine enough.

The fast-paced brutality of the world contrasts with the slow, stunted growth of Palestine, the one place on Earth that remains paused. This dead-end speed of the world mirrors the unlivable conditions created in Palestine today.

This is the reason behind my collection title, ‘Apocalyptic Rebellion الانقِلاب المُتَمَّرد’—we’re in the midst of an apocalypse, and the only way through it is rebellion.

Your work has been described as “boundary-less” in its ability to intertwine rebellion and emotional depth. What does boundlessness mean to you, and how do you push boundaries in fashion and art?

Vandalism. Vandalism. Vandalism.

For me, it’s second nature—leaving my mark on a world that tries to erase me. It goes beyond graffiti, into everything I do. Seeing clothes and metals I’ve designed interact with people’s bodies is a form of vandalism.

Vandalism can exist in many forms of disruption - however that translates to the individual and their capacity. If you’re a writer or lyricist, sharpen your pen. If you’re a music selector, saturate the spaces you’re in with our (Palestinian) sounds and instruments. If you’re a photographer, document our Palestinian youth no matter where they are in the world. If you’re a director, tell the stories of truth, no matter how brutal. However you rebel, do it fearlessly. Break the glass, burn the bridge, shatter all borders.

In a world designed to keep us restless, we have every right to disrupt it. Less curation, more entropy.

How do you balance artistic expression and activism in your fashion and art?

My political DNA will naturally take over my practice, message and artistry. I’m not an activist, I am, however, a storyteller, and my medium is my message. My work isn’t for those who daydream about what could have been home—I’m here for those who are actively working towards a liberated community one day. We all have access to weapons if we choose to understand that, mine are my mind and my hands.

As a perpetual learner, I translate experiences instantly. I also avoid overly curated expressions, which is why I love vandalism—it's raw, unfiltered, and live. No edits. I try to bring that spontaneity to all my work, whether in design, painting, or music.

The contrasting materials and textures in your work—such as hard metal and soft merino wool—symbolise the dualities you’ve experienced. Can you elaborate on the significance of these choices?

I play a lot with metals, it's my favourite element and textile - even sound. I admire when I see a final sketch turn into a full storyline where the design comes to life. Styling soft fabrics with hard textiles is a balance that mirrors my reality.

I seek discomfort when I create - my reality is uncomfortable, and I have no interest in producing work that is relatable or easily digestible, as long as it feels like me.

Your identity as a “21st-century Palestinian” is deeply rooted in your work. How does your cultural heritage shape the core themes and visual language of your art and fashion?

Visual interpretations of human anatomy is my chosen expression because it demands vulnerability and realism. Elements of stone, concrete and the colour red remind me of home.

My cultural heritage is rich—an Arab legacy of art, science, poetry—but my definition of being Palestinian is shaped by stories of apartheid, by bodies buried beneath our soil, by blood in our waters.

When you feel alienated from home, you create your own space. Yet, I often struggle to relate to others’ ideas of Palestine, as I’ve never known a liberated home. All I’ve experienced is what I’ve seen through the trauma that has affected the elders in my family, and through the refugee camps scattered all over Amman; broken families, a system designed to drown you as an individual, and displacement.

As an independent designer, how do you maintain creative control and authenticity in an industry that often prioritises commercial success and censorship?

You have to cultivate emotional autonomy, resisting outside pressure to rush a project. I need to be whole to tell my story. As I grow, I am becoming more comfortable in saying ‘time doesn’t intimidate me’, because I’ve grown to understand that my most meaningful work comes from taking my time and marinating in what I feel - and that in itself is rebellion.

You won’t make me feel inadequate because your definition of success is constant output. It doesn’t work on me. I know I have all the time I need.

Looking ahead, what are your aspirations for your work’s impact? How do you see it fitting into the broader landscape of Palestinian art, activism, and the creative industry?

I hope my work takes me home. I dream of working with Palestinians, on Palestinian stories, on liberated land. It’s a lifelong project - not just a dream.

Until then, I’ll work on sharpening my tools so that I can put them in practice when it's time to return and rebuild. True globalisation and liberation can only be achieved through collective effort — I don’t want to do this alone.

- Previous Article EXCLUSIVE: Hadia Ghaleb Launches Debut Eyewear Collection

- Next Article Monochrome Monday: The Electric Blue Edition