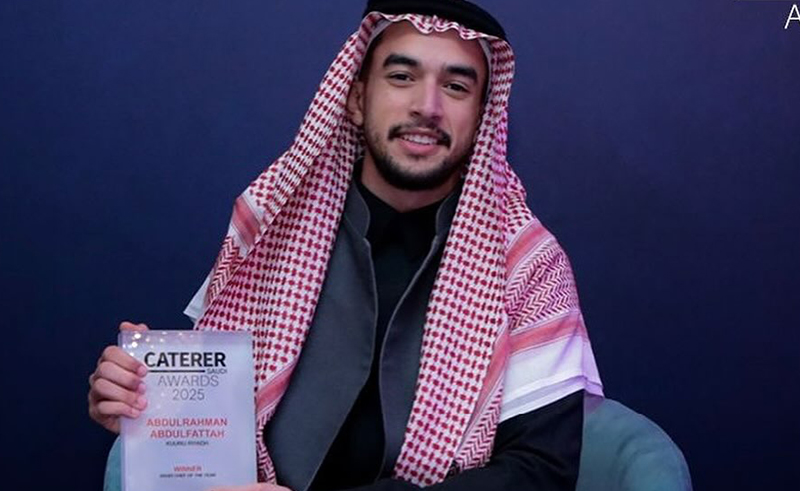

Saudi Chef of the Year Abdulrahman Abdulfattah is Hungry for More

From burnt spaghetti to Saudi Chef of Year, Abdulrahman Abdulfattah conquered allergies, stalked kitchens, and chose hunger over comfort.

In the gentle lull between lunch and dinner, when the kitchen exhales and the scent of garlic clings like memory in the air, a young man leans over a counter with the care of someone inspecting old love letters. His movements are measured, deliberate, attuned to the quiet rhythm of flour, sauce and spoon.

-22a4091a-3a9f-4002-8ebd-06b7803d447a.jpg)

The hands at work belong to Abdulrahman Abdulfattah, a 22-year-old whose fingers now carry dignified scars: nicks from ceviche knives in Lima, calluses from tandoors in Riyadh, and a grip tight enough to clutch the Saudi Chef of the Year trophy he won earlier this year. "You want to kill me? Keep me comfortable," he likes to joke—because comfort is the enemy of ambition, and Abdulrahman has no interest in staying still. But the story that led him here—Saudi’s youngest rising star in a field that once barely made room for men like him, at least in Saudi Arabia—is not one of straight-line success. It’s a story of smoke and self-belief, of one boy with a lifelong hunger to prove that kitchens don’t come with locked doors.

-d1fd4ee9-43c7-43a7-9283-8ef6b1ea0c14.jpg)

Every great chef has an origin story etched in flame and failure. For Abdulrahman Abdulfattah, it begins with a pot of burnt spaghetti when he was eight years old. "I left it to boil until the water evaporated," he says. The smoke came fast, and panic came faster. In the chaos, he scorched his mother’s brand-new kitchen counter — "a really black circle," he remembers — then tried to cover the evidence. It didn’t work. "My mom saw it and slapped me," he laughs. "She doesn’t remember, but I remember until now." Burnt carbs and life lessons.

The story’s funny in the telling, but in it lies a key to something deeper: his instinct to try, to mess up, to figure things out by doing. That same instinct would later push him to taste fish even when he was allergic — to sneak bites at family dinners, face flushed and throat tightening. "I used to feel very bad because I wanted to eat it and I saw everyone eating it, but I couldn't."

Years later, in Portugal, he faced a choice: eat rice for eight months, or risk fish. Antihistamines in hand, he chose the latter—sardines, shrimp, octopus—until, eventually, he stopped taking the pills. The symptoms softened, then disappeared. "I asked everyone—food safety teachers, directors—can someone cure himself of an allergy? They all said no. They think I’m lying. But ask my mom: I used to eat nothing. No fish at all."

Still, his love of seafood is just one thread in a much larger fabric. Abdulrahman’s culinary evolution sharpened during his time at Leylaty, a fine dining powerhouse in Jeddah known for its scale and prestige. “Leylaty was a turning point,” he says. “It taught me how to lead a team, how to keep calm under pressure, how to care about the smallest details even in the middle of chaos. We are doing hundreds of covers. You don’t forget that kind of pressure.”

From the beginning, the company had laid out the stakes. "I was told from the day I joined Leylaty that this company gives you the tools to grow," he recalls. “Either you enter as a commis and leave as a commis—or you enter as a commis and leave as a head or manager.”

He made himself a promise: to prove his worth not just for himself, but for those who would follow.

That restless hunger runs through everything Abdulrahman does. He’s the kind of cook who can casually conjure sellable dishes in real-time — like a pistachio sambosa that started as a joke and ended as a concept. Within seconds, he was designing it: "Make the mold with chocolate, fill it with pistachio, then paint it with edible paint… make it look like a fake sambosa, but it’s dessert."

By 15, while peers crammed textbooks, Abdulrahman was clocking shifts in a hotel kitchen, slicing onions until his eyes streamed. His mother’s Ramadan feasts had ignited his passion, but Saudi Arabia in the 2010s wasn’t ready for male chefs. "Even I thought it was haram. My best friend said, ‘Your family spent all this money for you to cook?’ So I stopped telling people. I decided to show them instead."

-bc14f771-bf7b-4f9b-8ab2-4b94a240f55f.jpg)

The pandemic became his pivot. A scholarship to study aeronautics engineering in Miami evaporated, leaving him with a "sign to chase cooking." When Swiss culinary academies were too costly, he hacked his own education: a year at a local Saudi academy, then an unpaid internship in Portugal, sleeping in a villa with 14 strangers. "No pay, no privacy—just 18-hour days learning to fillet fish."

In 2024, Abdulrahman turned stalker for the sake of Peruvian leche de tigre. He spammed Central, then the world’s top restaurant, with 100 emails. The last read: "I’ve booked a flight. If you don’t reply, I’ll camp on your doorstep." They relented, making him their first Saudi to intern in their kitchen.

-72a17270-e8a7-4f02-bb0a-97af5f099c77.jpg)

The experience became a turning point, not just for technique, but for belief. He came back sharper, steadier, hungry for more.

When his name was called at the Caterer Middle East Awards in 2025, where he was dubbed Saudi Chef of the Year, he froze. "I thought, ‘There are 100 Abdulrahmans here.’ But it was me."

The moment landed like punctuation — not an ending, but a pause "That trophy’s for my mom, my brother, my family" he said later.

-88221cf3-a160-4c0e-b9a0-a0e5d29a8e43.jpg)

Now, Abdulrahman’s attention is elsewhere. He’s opening a French restaurant with Leylaty— Lola—where he’s joined as sous-chef. He’s working on a sourdough starter at home. He eats a lot of ice cream.

"Teamwork is the most important thing in the kitchen," he says. "You don’t get anywhere without it." He dreams of being a ‘Jack of All Trades’, or rather ‘The Abdulrahman of All Trades’. He wants to be the face of Saudi culinary culture, not boxed into a single cuisine but fluent in many. "I want to be the Gordon Ramsay of Saudi Arabia," he says, then quickly laughs.

-31efdd74-9768-4bd9-bb81-493dd4ee2697.jpg)

That ethos of collaboration, generosity was shaped by mentors who guided him at pivotal moments of his career. In his days at Kuruu, chefs Eddie Castro and Kenji Sarko instilled foundational lessons. “I wouldn’t be who I am without them,” he says. “Kenji taught me to focus on my health—mental and physical. Eddie taught me to never stop asking questions. They’ve left their DNA in me.” Abdelfattah also found himself influenced by Chef Claudio Cardoso, a Portuguese culinary director with decades of experience in Michelin-starred kitchens and a vast global network. “He opened my brain a lot,” Abdulfattah reflects. It was Claudio who championed his leap of faith to work at the world’s best restaurant. “If I observe his brain a lot I believe, I will be able to reach whatever I want to reach in no time.”

Abdulfattah’s mantra? “Wanting to learn isn’t enough—you have to need it.” He’s the chef who asks “Why?” until mentors snap, the intern who voluntarily debones fish on his days off. “Mistakes are lessons. Make one twice? That’s stupidity.”

In a region where culinary revolutions are often imported, Abdulfattah is homegrown—a chef proving that hunger, like good harissa, only intensifies with time.