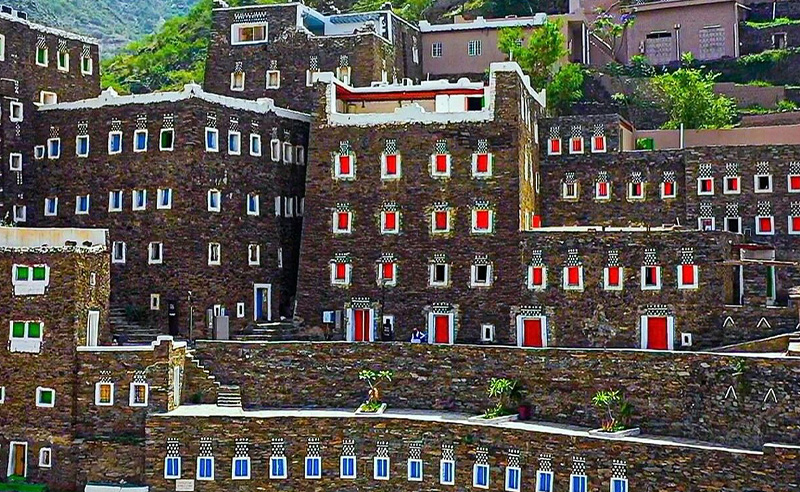

This Ancient ‘Gingerbread Village’ Is Carved Into Saudi’s Mountains

A 400-year-old village of high stone houses, painted windowpanes, and a past etched in trade.

The road from Abha descends through the Asir mountains, curving past ridges softened by mist and valleys stitched with green terraces. Some fifty miles from the city, at the base of a steep incline, lies Rijal Almaa—a village so quiet, so composed, it seems to have emerged fully formed from the stone itself.

At first glance, you might miss it. The buildings—tall, stacked, angular—cling to the earth like outcrops, their forms echoing the rhythm of the hills. But then the road straightens, the valley opens, and the village reveals itself in full: towers of stone and clay, rimmed in white, their windows catching the sun like mirrors.

For centuries, this place was a resting point—traders passing through from Yemen to the Levant, pilgrims on their way to Makkah and Madinah. The village rose from the necessities of exchange, of shelter, of spiritual pause. Yet what was built here went beyond utility.

Today, Rijal Almaa feels less like a crossroads and more like a memory preserved in architecture.

There are roughly sixty buildings in the village, many of them rising five, six, even eight stories high. Constructed from dark stone, clay, and wood, the structures are sometimes called "forts," though their elegance makes the word feel too blunt. The façades are studded with white crystal stones. Inside, the walls bloom with Al-Qatt Al-Asiri—a form of geometric mural painting passed down through generations of women. The colours are bright, sometimes clashing, always intentional. The effect is one of quiet rebellion: a burst of expression inside walls meant to keep the desert out.

At the center of it all is the Rijal Almaa Heritage Museum, housed in what was once the Al Alwan Palace. Over four centuries old, the building now contains more than 2,000 artifacts—manuscripts, tools, weapons, objects from lives once lived here.

Though time frayed its edges, the village never truly disappeared. In recent years, restoration efforts—led by national bodies and supported by the local community—have brought Rijal Almaa into the present without sanding down its character. An open-air theater now hosts performances against a backdrop of stone towers; green spaces spread where once there were only rocks. In 2021, the World Tourism Organization named it one of the best tourism villages in the world. It remains on Saudi Arabia’s tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage status.

Despite everything, the feeling Rijal Almaa leaves is older than any plaque or award. Visitors walk narrow alleys where camels once passed. They see the mountains framed through windows once opened to catch the evening light. They move through a village where everything—the towers, the art, the quiet—is still speaking, if you know how to listen.