When the Tarboush was the Crown of Egypt’s Sovereigns

The proud tarboush was once a glittering symbol of grandeur during the Kingdom of Egypt, worn proudly by both the sovereign and government bureaucrats.

In a not-so-distant past, Egypt was ruled by a decadent, extravagant, and supremely stylish elite of royalty, aristocrats, and industrialists. Cairo, once known as "Paris on the Nile," was a city of grand, tree-lined boulevards, picturesque gardens, and stately homes. Opera houses and royal palaces illuminated the night in brilliant swells of light, while the city’s legendary café culture thrived on the patios and porticos of the Gezira Club and the Azbakeya Gardens. High fashion was the order of the day, and it was unthinkable for any Pasha, Bey, Nabil, or Prince to be seen in anything less than the whitest linen suits, silken paisley ties, and the chicest leather brogues. But while the Egyptian elite dressed in the same elaborate outfits as their counterparts in Rome, Paris, and London, one element set them apart—the ever-present, proud, burgundy tarboush perched atop the head of any distinguished gentleman.

King Farouk with Princes of the Royal Family and Cabinet Ministers

King Farouk with Princes of the Royal Family and Cabinet Ministers

The tarboush, originally brought into vogue in Egypt by the Ottoman nobility who ruled during the early days of Mohamed Ali Pasha, took on a distinctly Egyptian character during the reigns of Khedive Ismail and King Fouad. Once a small, rounded cap, the Egyptian tarboush evolved by 1917 into a tall, conical piece made of deep burgundy wool or silk, reinforced internally by straw. The more fashionable the Pasha, the more slanted his tarboush would be, signaling the gentleman's debonairness and lending him an air of bohemian worldliness. Some avant-garde nobles wore their headpieces so slanted that one might expect them to fall at any moment. Renowned journalist Samir Rafaat noted in his 1996 article ‘The Tarboosh: And the Turco-Egyptian Hat Incident,’ published in the Egyptian Mail, that “Crown Prince Mohammed Ali Tewfik wore it in a manner defying gravity, looking like it was about to topple over at any moment.” More artistically inclined gentlemen, like Mohamed Abdel Wahab and Youssef Wahbi, often allowed the silken tassel—usually affixed to the back of the tarboush—to hang softly off the side of their headpiece.

Prince Mohamed Ali Tewfik

Prince Mohamed Ali Tewfik

King Fouad I of Egypt and the Sudan with King George V of the UK During a State Visit to the UK

King Fouad I of Egypt and the Sudan with King George V of the UK During a State Visit to the UK

Youssef Wahbi

Youssef Wahbi

with Youssef Wahbi (right)-6538326c-2a93-4913-a435-4ef1089bdd83.jpg) Oum Kalsoum (left) with Youssef Wahbi (right)

Oum Kalsoum (left) with Youssef Wahbi (right)

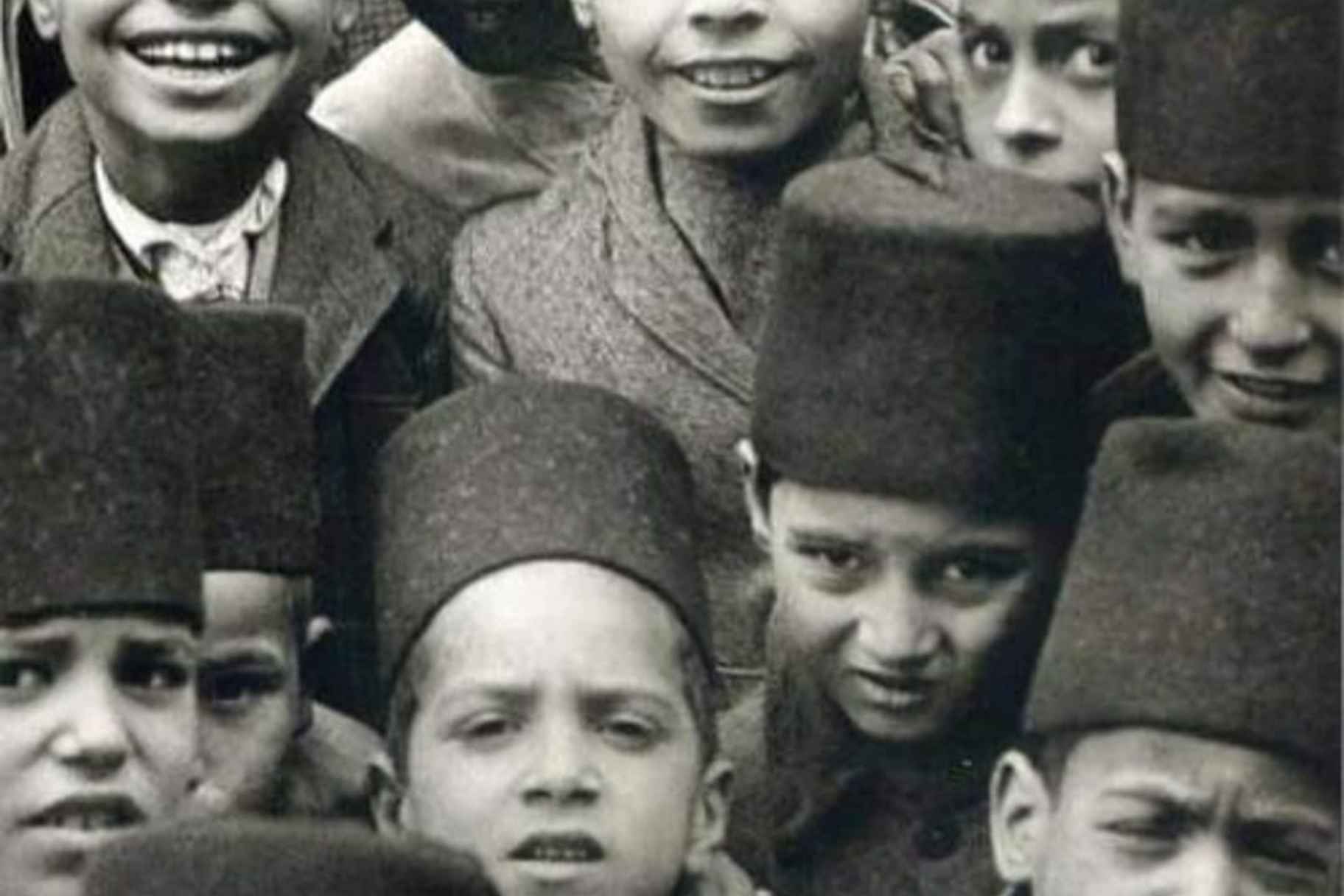

The tarboush became a symbol of the unique decadence of the Egyptian royal court, akin to how peacock dishes epitomized the extravagance of the Persian royal court or how bejeweled Fabergé eggs represented the excesses of the Russian monarchy. It was worn with pride by any well-dressed gentleman, regardless of class, as an imitation of what was portrayed as elegant and patriotic by the image of the sovereign and his aristocracy. Thus, the tarboush found its way into the wardrobes of the educated effendi class, which emerged as Egyptians gained greater access to tertiary education during King Fouad I's reign.

Egyptian school children

Egyptian school children

As the sovereign of Egypt was also regarded in the Muslim world as the Caliph, the tarboush became a religious symbol, and for a time, it was popularly believed to be required garb during daily prayers. The sheikhs of Al Azhar would wrap a white turban around their tarboush to signify their scholarly pedigree as students of the world-renowned institution of Islamic law. Yet, the tarboush was a non-denominational affair, worn with pride and flair by members of all of Egypt's diverse religious and ethnic communities—from Catholic Levantine businessmen to Jewish financiers, and from Armenian photographers to Coptic Orthodox merchants. Egyptian Jews, in particular, who were religiously required to cover their heads during prayer, often chose the tarboush over the smaller skullcaps worn by Jews in other parts of the world. The tarboush thus became a unifying symbol, transcending socio-economic and religious differences, and representing the unity of the Egyptian people.

Egyptian Jews attending a bar mitzvah at a synagogue in Cairo

Egyptian Jews attending a bar mitzvah at a synagogue in Cairo

With the end of the Kingdom of Egypt following the Free Officers’ coup of 1952, the tarboush was demonized by the new Republican government as a symbol of the decadence, foreignness, and extravagance of the ancient régime of King Farouk and his predecessors. The government formally banned the once-popular tarboush, along with the honorific titles of its wearers. Yet, in the popular memory, preserved through old family photographs, black-and-white films, and a nostalgia for the cosmopolitan monarchy, the tarboush remains a symbol of a bygone elegance and glamour.